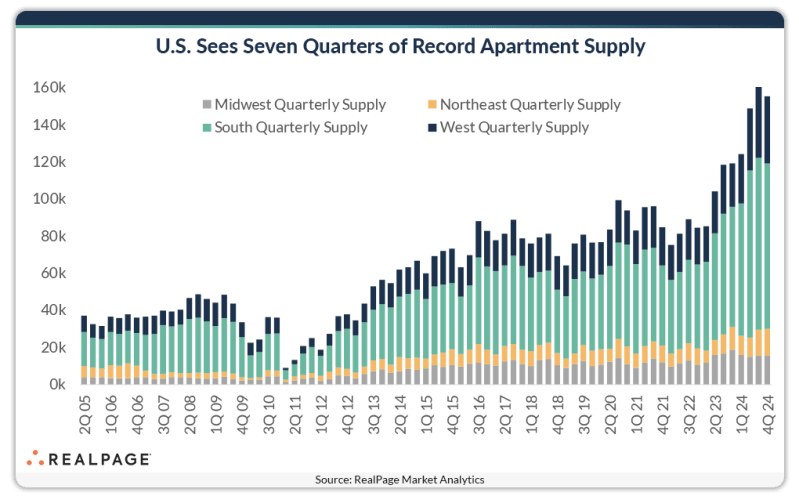

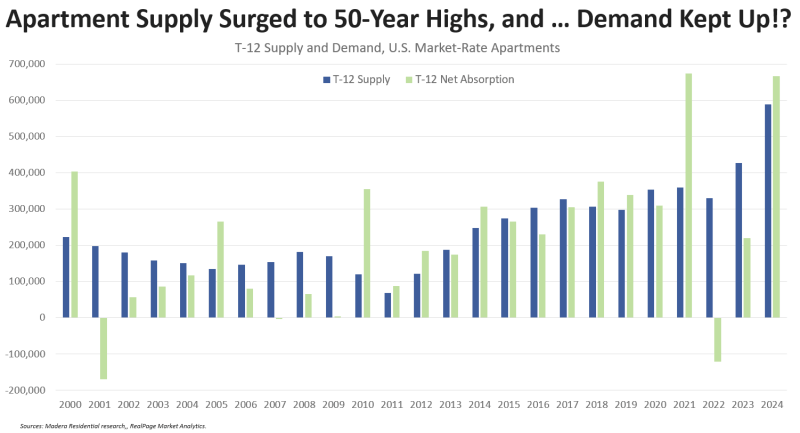

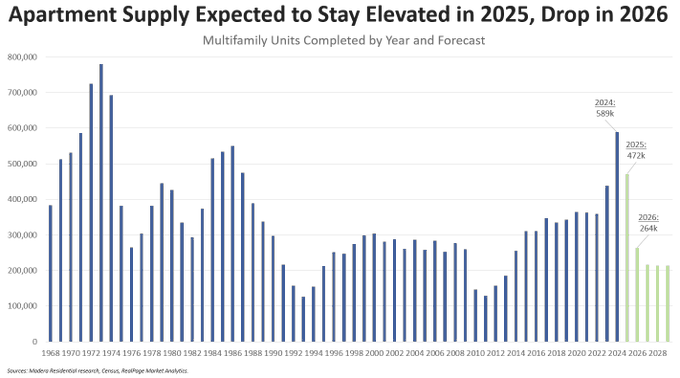

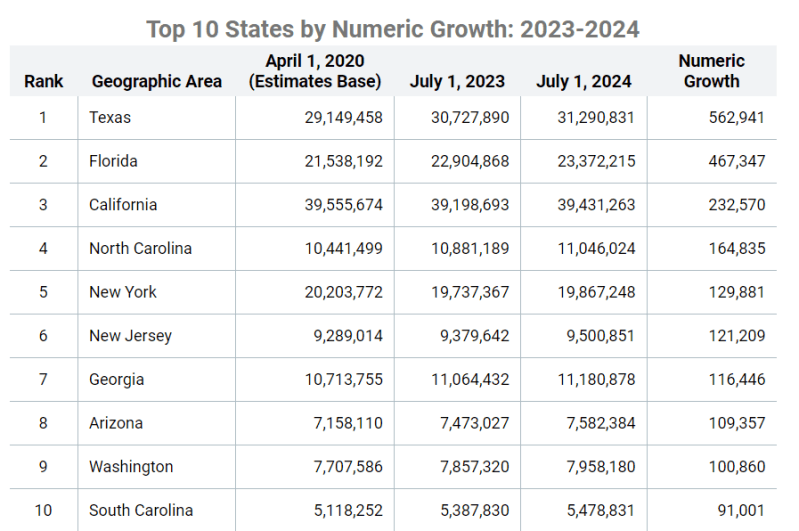

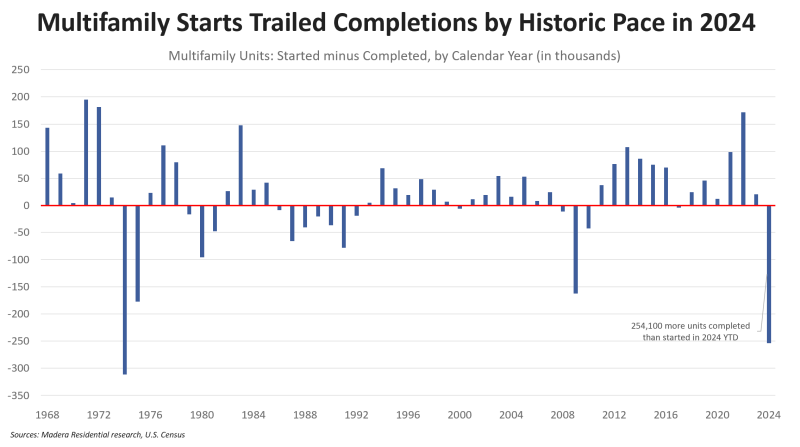

Final numbers for 2024: Multifamily builders started 254,100 fewer units than they completed. That’s the second-biggest deficit on record, behind only 1974. And it’s yet another clear indicator that new apartment supply will plunge by 2026.

__________________________________________

Article from Jay Parsons on the scary multifamily starts number released for December (causing the market to be concerned about an unexpected increase in new supply):

Seeing headlines about a December “surge” (by 62%!) in multifamily construction starts, based on today’s Census data release. It’s a mirage. There is no such spike. It’s just a methodology quirk resulting from how the Census annualizes “seasonal adjustments.” On a NON seasonally adjusted basis, the month of December 2024 came in lower than any December since the pandemic year of 2020. The Census seasonal adjustments always show wild, volatile swings in multifamily starts. It’s never been useful indicator.

__________________________________________

From This Week’s Pensford Letter – 1/21/2025

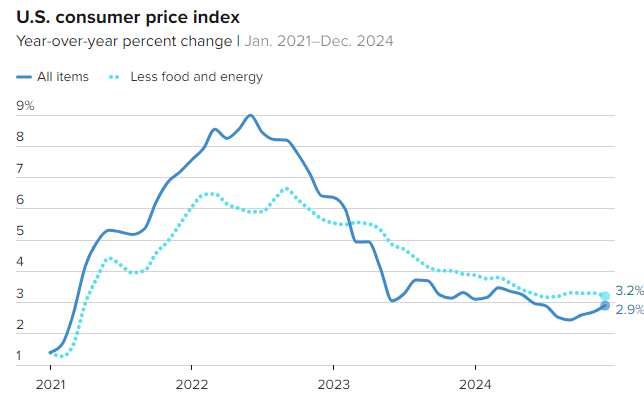

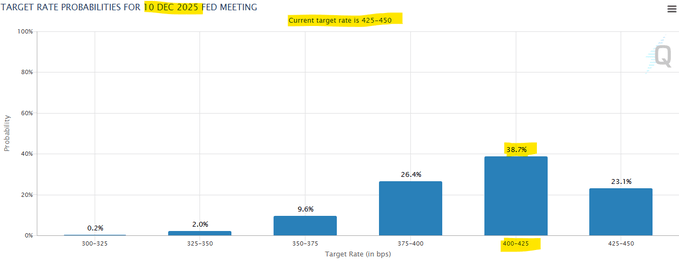

CPI has several components that feed directly into Core PCE, so economists always rush to update their PCE forecasts with greater accuracy. WSJ Fed-whisperer Nick Timiraos compiled some revised forecasts for the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, and the m/m Core PCE is just 0.17%. That annualizes to just over 2%.

__________________________________________

From Nick Timiraos this week (considered the mainstream media’s voice for the Federal Reserve):

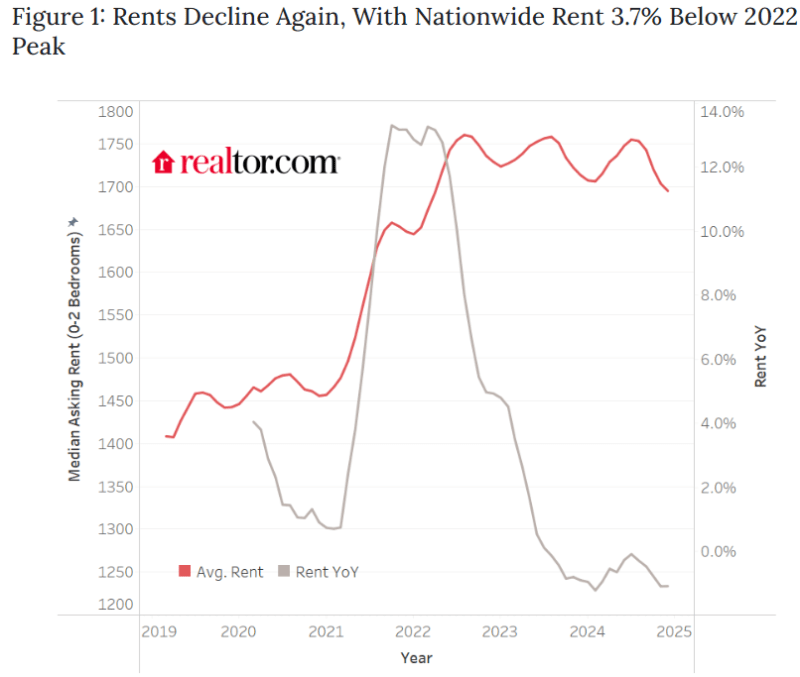

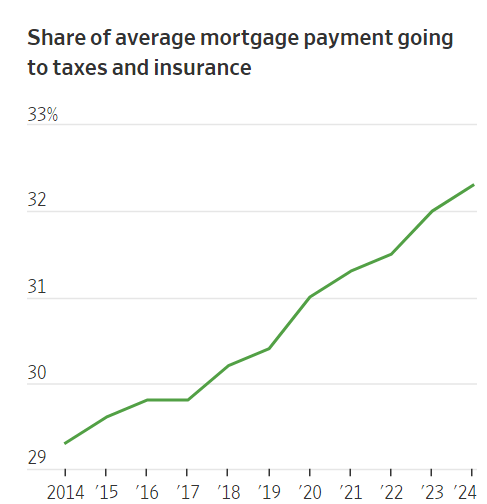

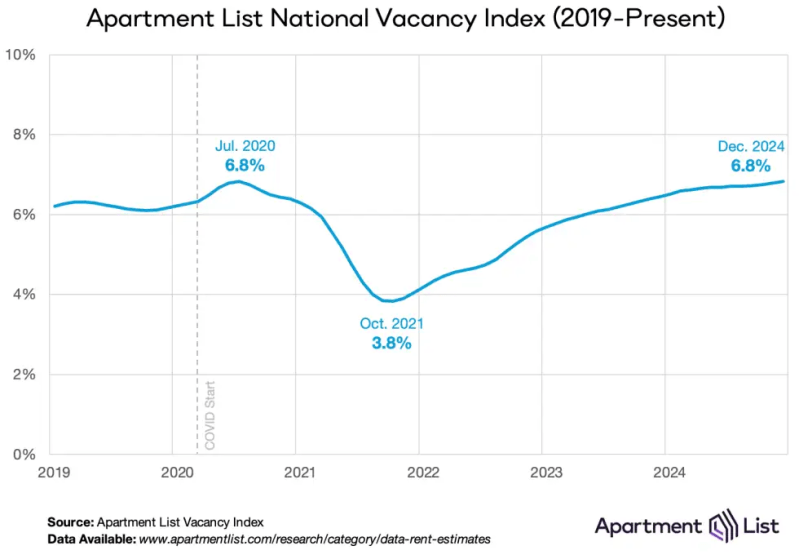

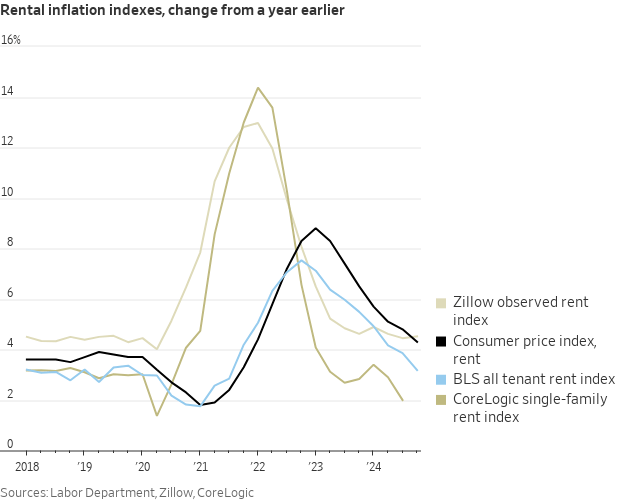

“CoreLogic reports single-family rent growth was up 1.5% for the year, the smallest increase in 14 years. Another data point today suggesting ongoing shelter disinflation is in store for the (lagged) official government measures.”

The Labor Department’s “all tenant rent” index, which leads shelter inflation in the CPI, rose at a much slower pace last quarter. It was up 3.2% over the four quarters ended Q4 (vs. 3.9% in Q3 and 5.5% one year ago). It’s very close to the 3.1% average between 2017-19.”

____________________________________

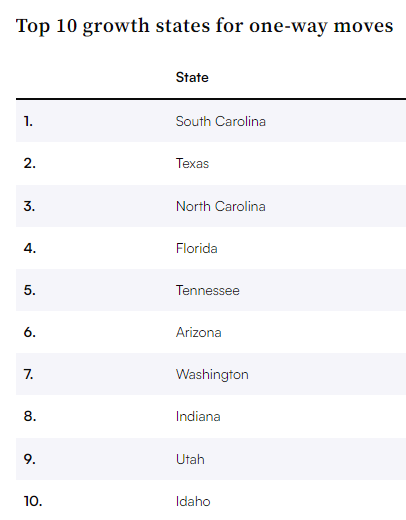

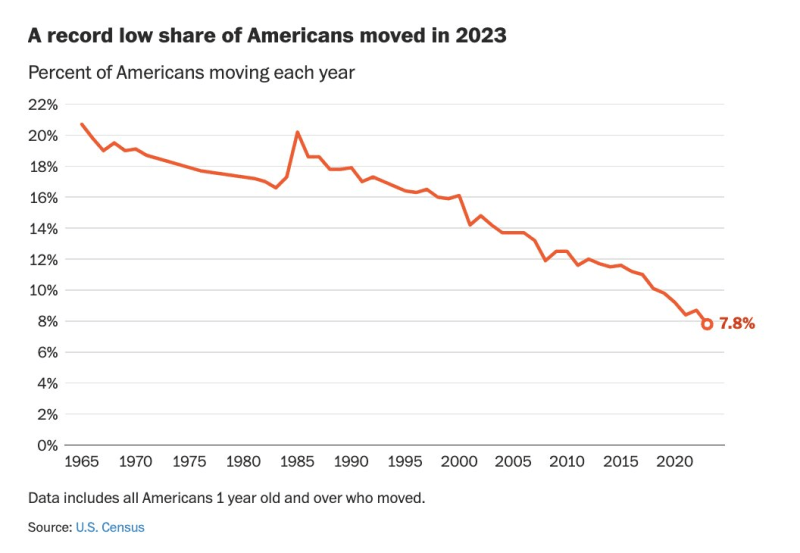

In the ‘Great Stay’ economy, Americans feel stuck. Hiring right now is anemic (esp. outside healthcare & gov) People aren’t moving. Promotions and bonuses are down. People even keep cars for record time. People feel cemented in place.

What it means: A weaker jobs market makes the Fed more likely to cut interest rates.

__________________________________________

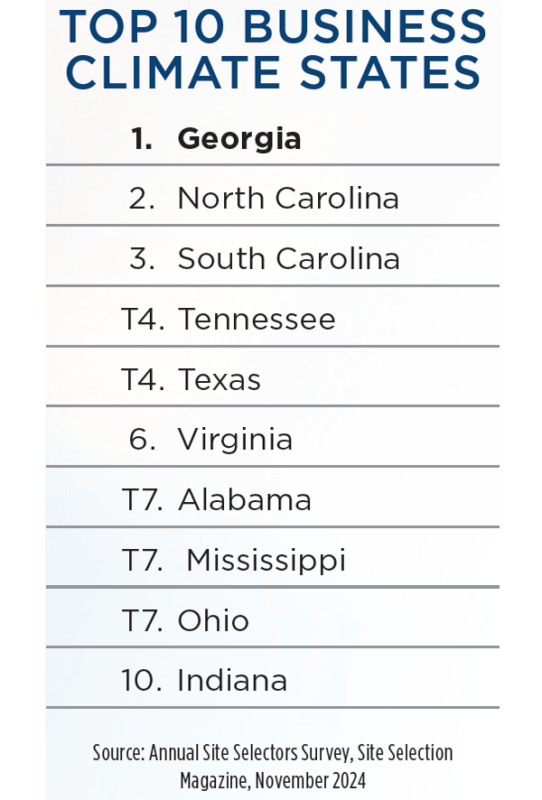

Per JP Morgan, politics historically have little impact on commercial real estate returns. It’s always about the economy.