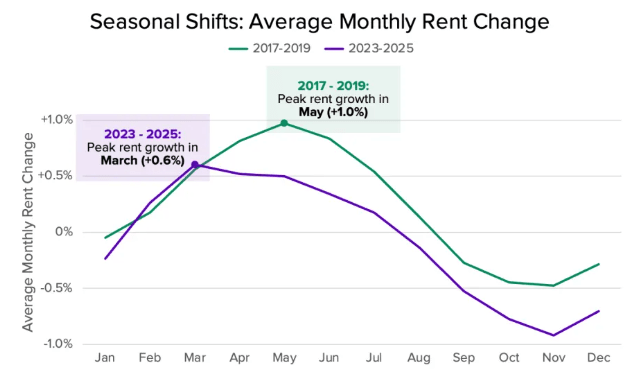

The rental market tends to follow an established seasonal pattern. More people generally move during the spring and summer, and rent prices normally rise accordingly as multifamily operators increase rents in response to the spike in demand. During the fall and winter months we tend to see the opposite: less moving activity, and operators pulling back on rents to attract the dwindling set of renters still on the market for a new home.

This seasonality results from three practical factors: school, weather, and holidays. The summer is more favorable for all three: if you are a student or have young children, you don’t need to juggle school schedules; weather is generally more temperate; and moving expenses aren’t being eaten up by holiday spending. Renters who have the flexibility and means to relocate during the winter will generally find lower prices and more wiggle room for negotiating lease terms.

Over the past three years, we’ve seen a noticeable shift in the timing of this seasonality. Since 2022, rental activity is more evenly distributed throughout the calendar year, annual rent declines exceed annual rent increases, and peak rent growth has moved up earlier in the year.

From 2017-2019, the typical seasonal pattern was this: nationwide rents would rise for seven months from February through August, with peak rent growth (+1.0 percent) occurring in May.

Since 2023, there has only been six months of rent growth each year, from February through July, with peak rent growth down to +0.6% and occurring two months earlier in March.

These shifts are due to a combination of factors including:

- The persistent impact of a one-time shock to the timing of moves due to the pandemic

- An intentional shift by multifamily operator to spread out lease renewal dates

- A supply rich environment offering renters more optionality and flexibility in their moves

Source: ApartmentList